This week, teaching Dracula, I had the pleasure of re-reading Sigmund Freud’s essay on the uncanny, a thing described by Freud as ‘that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar’ (p.219).*

Why would ‘old and long familiar’ things ever be frightening, you may well ask? Freud puts together a somewhat more comprehensive summary of the term towards the end of his essay, stating:

In the first place, […] among instances of frightening things there must be one class in which the frightening element can be shown to be something repressed which recurs. […] In the second place, if this is indeed the secret nature of the uncanny, we can understand why linguistic usage has extended das Heimliche [‘homely’] into its opposite, das Unheimliche [‘uncanny’]; for this uncanny is in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression. (p. 240)

According to Freud, repression is the basis of a great deal of anxiety, and in the case of the uncanny, it is precisely the return of this repressed thing that causes fear. Basically, then, for some of the things we are afraid of, we don’t actually fear them because we don’t recognise them, or because they are completely alien, but rather because we can actually link them to something very familiar, that we can’t quite put our finger on. That makes us uncomfortable.

For Freud, ‘these themes [of uncanniness] are all concerned with the phenomenon of the “double”, which appears in every shape and in every degree of development’ (p. 233). This doubleness can take many different forms. It can be found in reflections, in people and places who look the same, in déjà vu. It can be created by parallel plots and events and spaces. It is coincidence embodied.

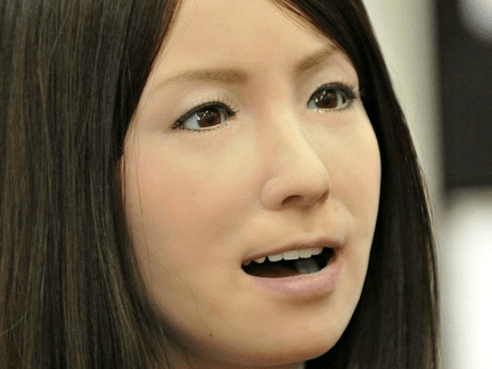

Looking at more specific examples of the uncanny, Freud suggests that ‘a particularly favourable condition for awakening uncanny feelings is created when there is intellectual uncertainty whether an object is alive or not, and when an inanimate object becomes too much like an animate one’ (p. 232). We find Cao Hui’s fleshy chair uncanny not just because it is disturbing to look at, but because we’re not quite sure how it would feel to touch it. It might seem too much like human flesh to the fingers, as well as to the eyes.

In other words, though we know we are looking at a sculpture, we still can’t quite shake the discomfort it instills in us. Freud underlines this point as well, describing how the uncanny resists the power of the rational mind:

There is no question therefore, of any intellectual uncertainty here: we know now that we are not supposed to be looking on at the products of a madman’s imagination, behind which we, with the superiority of rational minds, are able to detect the sober truth; and yet this knowledge does not lessen the impression of uncanniness in the least degree. (p. 229)

The uncanny draws its power from the repressed and the unconscious. It doesn’t fit within what the rational mind knows, but can’t be shaken off so easily. It is rationally familiar, yet still eerily unfamiliar.

I’ve always found Freud’s essay to be rather uncanny in itself, with lots of repetition and doubling, and many observations that are just plain weird. Take this gem, for instance:

We know from psycho-analytic experience, however, that the fear of damaging or losing one’s eyes is a terrible one in children. Many adults retain their apprehensiveness in this respect, and no physical injury is so much dreaded by them as an injury to the eye. We are accustomed to say, too, that we will treasure a thing as the apple of our eye. A study of dreams, phantasies and myths has taught us that anxiety about one’s eyes, the fear of going blind, is often enough a substitute for the dread of being castrated. (p. 230)

There’s a lot to unpack in this quotation. My first impulse, however, is just to be terribly curious about the children from whom Freud gained his ‘psycho-analytic experience’, who led him to believe that their fear ‘damaging or losing’ their eyes was ‘a terrible one’. What awful stories did they tell him, and what awful questions did he ask to elicit said stories?

Thanks very much Freud. Now I have a terrible fear as well.

Another of the joys of discussing the uncanny was that it allowed me to bring in lots of images, many of which are included in this post. The uncanny is everywhere in twenty-first century culture (just as it was, I imagine, in Freud’s own nineteenth century context).

How did all this relate to Dracula, though? Somewhat tenuously in the case of my seminar, but quite neatly in criticism more generally. Traditionally, monsters like the vampire are uncanny figures – though not the only kind, of course – and they make the texts the appear in uncanny too. We are not sure quite where to place them, and they make us uncomfortable, particularly because the ways in which they are uncanny or other tend to be ‘cultural, political, racial, economic, sexual’, as Jeffrey Jerome Cohen puts it in his seminal essay ‘Monster Culture’ (p. 7).

This uncanniness disrupts the neatly ordered reality we construct for ourselves, and the neatly ordered texts in which such monsters often find themselves. Cohen describes the potential of monsters as follows:

The horizon where the monsters dwell might well be imagined as the visible edge of the hermeneutic circle itself: the monstrous offers an escape from its hermetic path, an invitation to explore new spirals, new and interconnected methods of perceiving the world. In the face of the monster, scientific inquiry and its ordered rationality crumble. The monstrous is a genus too large to be encapsulated in any conceptual system; the monster’s very existence is a rebuke to boundary and enclosure (Cohen, ‘Monster Culture’, p. 7)

Uncanny monstrosity arguably represents one way that literature can help us to imagine new ways of thinking and being. It represents reality and identity, but never quite. The monster is the dark double of the normal and the rational, the return of the repressed, and the unfamiliar in the familiar.

*All references to Freud refer to ‘The Uncanny’ in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis & Other Works, 217-256.