This post originally appeared on the Victorianist, the postgraduate blog of the British Association for Victorian Studies, on 18 May 2015. It is reposted here with the kind permission of the editors.

I should probably preface this post by admitting that I’m not a real Victorianist. The Victorians were one of my undergraduate passions, and I continued to read and write all about them during my MA, but somehow I was always more interested in how we speak about the Victorians today than in how they actually spoke to themselves or to us. It was the fantasy of the Victorians that I found most intriguing. For the purposes of today’s post this works out well, because although the texts and subcultures I’m currently researching are often set in the nineteenth century, borrowing Victorian politics and aesthetics, they aren’t really Victorian either.

Specifically, I’m talking about the monster mashup, in this case the kind that appropriates objects, texts and contexts from the long nineteenth century and combines them with a very twenty-first century monster culture. These mashups come in many flavours, and can be found in virtually every artistic medium. You’ve got computer and console games like Fallen London or The Order: 1886. There are monster mashups in film and television, like Van Helsing (2004) and Showtime’s Penny Dreadful (2014). They’re also in the fine arts, and a rich selection of monster mashups found themselves displayed at the recent Victoriana: The Art of Revival exhibition in 2013.

You’ll also find monster mashups, perhaps more predictably, among the ranks of comics and graphic novels – consider Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999) or Pinocchio, Vampire Slayer (2009). And of course there are novels, like Kim Newman’s Anno Dracula (1992|2011) or Cherie Priest’s Boneshaker (2009). Arguably the best-known monster mashup in novel form is the ‘novel-as-mashup‘, popularised with 2009’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies and continuing with such groan (or grin) provoking titles as Wuthering Bites (2010) and Grave Expectations (2011). These mashups lift the very words, sentences, and chapters from the texts they appropriate, changing a word here, a paragraph there to create a new (if ultimately very similar) text. From lowbrow to highbrow, drama to comedy, there’s a monster mashup for everyone.

The targets of these mashups aren’t exclusively from the nineteenth century, but an overwhelming number have thus far turned to the Regency and Victorian eras of Britain’s literary history for their source material. Copyright laws are no doubt partly responsible for this, as is the fact that we’ve got so much physical and visual material to draw on from the nineteenth century onward. The public education system is another likely culprit, as the most popular mashups (and the ones that attract the most media attention) tend to involve the classics of art and literature that most children in the Anglo-American world are introduced to during their early education. These are also the texts that have been kept alive by a seemingly endless series of adaptations, whether on the stage, by the BBC, or in cinemas.

A few weeks ago one of my fellow Cardiff PhDs, Daný van Dam, shared a post on Gail Carriger’s ‘Parasol Protectorate’ series (2009-2012), another monster mashup set in Victorian London. She wrote the following about the series’ Victorian appropriations:

Like many other neo-Victorian novels, Carriger’s books return not so much to the Victorian period and its history as to contemporary ideas about the Victorians, projecting present-day concerns upon an earlier period.

The precise nature of the relationship between neo-Victorian fiction and the past it references is something neo-Victorian studies is very interested in. In her book History and Cultural Memory in Neo-Victorian Fiction, Kate Mitchell puts the situation this way:

‘The issue turns upon the question of whether history is equated, in fiction, with superficial detail; an accumulation of references to clothing, furniture, décor and the like, that produces the past in terms of its objects, as a series of clichés, without engaging its complexities as a unique historical moment that is now produced in a particular relationship to the present. […] Can these novels recreate the past in a meaningful way or are they playing nineteenth-century dress-ups?’ Kate Mitchell, History and Cultural Memory in Neo-Victorian Fiction: Victorian Afterimages (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 3.

With the monster mashup, answering this question is usually fairly straightforward: this is clearly a case of dress-up. In appropriating historical texts and contexts, these overtly fantastical monster mashups don’t necessarily seek to restore or revise the past, but rather to bring it back to life as a new text, and in a new context. They are twenty-first century texts in a Victorian coat. Regardless of their apparent superficiality, these kinds of creations and discussions are important in postmodern culture. Dress-up and performance serve their own purposes, and nostalgia can be an end as well as a means.

Postmodern theorist and critic Fredric Jameson has frequently returned to the subject of historicity and nostalgia in his work, often in conjunction with utopia. Both nostalgia and utopia, he argues, paradoxically evoke a kind of perpetual present by fetishising either the past or the future. Unfortunately, both are doomed to creative and subversive failure – nostalgia because its narrative of the past ultimately only serves to circumscribe the present, and utopia because its totalising narrative of the future inevitably morphs into dystopia. It is the failed deployment of these two elements that has resulted in postmodernism’s stagnation or end of history.

Nevertheless, Jameson continues to pursue these twin impulses of utopia and nostalgia, aiming to contribute to:

[T]he reawakening of that historicity which our system – offering itself as the very end of history – necessary [sic] represses and paralyzes. This is the sense in which utopology revives long dormant parts of the mind, organs of political and historical and social imagination which have virtually atrophied for lack of use, muscles of praxis we have long since ceased exercising, revolutionary gestures we have lost the habit of performing, even subliminally.

For Jameson, in other words, though nostalgia and utopia are both doomed to failure and stagnation, the urge to imagine, to fantasise, and to create using these impulses remains vitally important. In this sense the creation of history-saturated fantasies is much more for the sake of present-day culture than it is an homage to history. Neo-Victorian fantasies help keep both history and imagination alive in popular culture, giving them a much-needed stretching.

As a side effect of the way they ‘stretch’ history, monster mashups also manage to revitalise history, mythologise it, and even change it in a sense. These texts encourage discussion between disparate groups of people. They also force old texts into new contexts, revealing our historical and hermeneutical distance from (and closeness to) the old contexts. This recontextualisation of the Victorians can sometimes have productive results.

To give one example, these reality-blurring and genre-bending monster texts often draw attention to the constructed nature of the self, and the problems inherent in contemporary representations of identity and otherness. Monstrous others have stood in for racial, sexual, and social minorities for hundreds of years, but in the words of Judith Halberstam, in contemporary Gothic the monster is no longer totalising:

The monstrous body that once represented everything is now represented as potentially meaning anything – it may be the outcast, the outlaw, the parasite, the pervert, the embodiment of the uncontrollable sexual and violent urges, the foreigner, the misfit. The monster is all of these but monstrosity has become a conspiracy of bodies rather than a singular form.

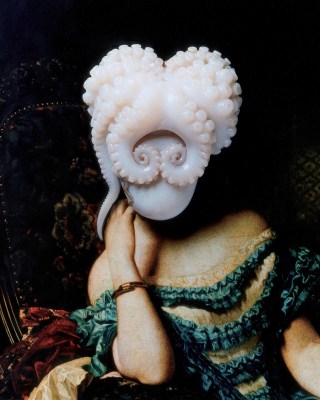

In contemporary Gothic, monsters are us, and we are all monstrous. In any case, through this ‘conspiracy of bodies’, neo-historical monster mashups can call out cases of imperialism, colonialism, or patriarchy without singling out a particular minority victim. Monsters represent otherness, but not a particular Other. Symbolically they oscillate between the centre and the margins, endlessly deferred. Consider Travis Louie, for example, with his fantastical portraits of Victorians. These both call us to identify with the characters they depict and present those characters as alien. Louie has a whole series of these ‘Victorian cryptozoology‘ images as well, which evoke discourses of imperialism and colonialism.

Naturally this oscillation doesn’t automatically mean that using monsters in mashup texts is unproblematic. Specific monsters are still socially marked in different ways – the homoerotic male vampire, the sexy female robot, the lower-class zombie – but monsters do add a layer of mediation, a buffer between audience and story. Texts like these open discussions of otherness that might otherwise be met with resistance or increasingly negative accusations of ‘political correctness’. And, as always, imagining difference in the past potentially creates space for difference in the present. History and its cultural traces provide the foundations and reference points for today’s ideologies.

Roland Barthes has a great deal to say about the way history and tradition become myth. For Barthes, mythologies are formed to perpetuate an idea of society that adheres to the current ideologies of the ruling class and its media. Mashups, as part of the domain of popular culture, certainly contribute to the perpetuation of society’s myths (the nation, heterosexuality, gender, etc.). They are rarely subversive in the traditional sense, but because of their appropriative nature it is difficult for anyone to control which ideas and ideologies are communicated to audiences and readers. There is always ample room for divergent interpretation.

In writing about the process of mythologisation, Barthes also refers to the tendency of socially constructed notions, narratives, and assumptions to become ‘naturalised’ in the process, or taken unquestioningly as given within a particular culture. Monstrous or fantastical history inherently resists such naturalisation, because it refuses to be taken entirely seriously, though certainly possible to politicise it. Monster mashups make history strange – or sometimes reveal the strangeness of history. Kim Newman has claimed that he initially decided to write Anno Dracula in response to Thatcherism and the rise of neo-Victorian political sentiment in the late 80s. This novel describes a Victorian England in which Dracula had succeeded in Bram Stoker’s novel, and come to rule over Great Britain. In this alternate history, which can be read as ironically similar to our own, Newman re-evaluates stereotypically ‘Victorian values’ as monstrous, ultimately showing that we often see what we want to see where the Victorians are concerned.

In writing about the process of mythologisation, Barthes also refers to the tendency of socially constructed notions, narratives, and assumptions to become ‘naturalised’ in the process, or taken unquestioningly as given within a particular culture. Monstrous or fantastical history inherently resists such naturalisation, because it refuses to be taken entirely seriously, though certainly possible to politicise it. Monster mashups make history strange – or sometimes reveal the strangeness of history. Kim Newman has claimed that he initially decided to write Anno Dracula in response to Thatcherism and the rise of neo-Victorian political sentiment in the late 80s. This novel describes a Victorian England in which Dracula had succeeded in Bram Stoker’s novel, and come to rule over Great Britain. In this alternate history, which can be read as ironically similar to our own, Newman re-evaluates stereotypically ‘Victorian values’ as monstrous, ultimately showing that we often see what we want to see where the Victorians are concerned.

In a discussion of the Neo-Victorian graphic novels of Alan Moore, also extremely political, Jason B. Jones argues that what makes such mashups subversive is not their disregard for literary categories or forms, but their potential redefinition of our very identities and cultural spaces. He states: ‘[s]uch game playing foregrounds the extimate aspects of historical change, as something neither wholly external nor subjective’. In other words, texts that mix history and fiction while also playing with genre convention make the reader more readily aware of the constructed nature of even the most serious history.

1 thought on “Victorian Monsters? Strategies of Appropriation in the Neo-Victorian Mashup”