As part of my forthcoming book project, I’ve been revisiting the Penny Dreadful series and comics. This included looking back at my online reviews of the show’s third and final season, which I will be posting here over the coming weeks. This post originally appeared on The Victorianist, 17 June 2016. It has been edited and corrected for reposting.

What does it mean to be true to yourself? What does it mean to be a good person? These are questions Penny Dreadful has frequently explored over its three seasons, but I’m not sure they ever felt as pressing or disturbing as they do in ‘Ebb Tide’. More than anything, the episode seems to suggest that the answers to these questions depend entirely on the person asking.

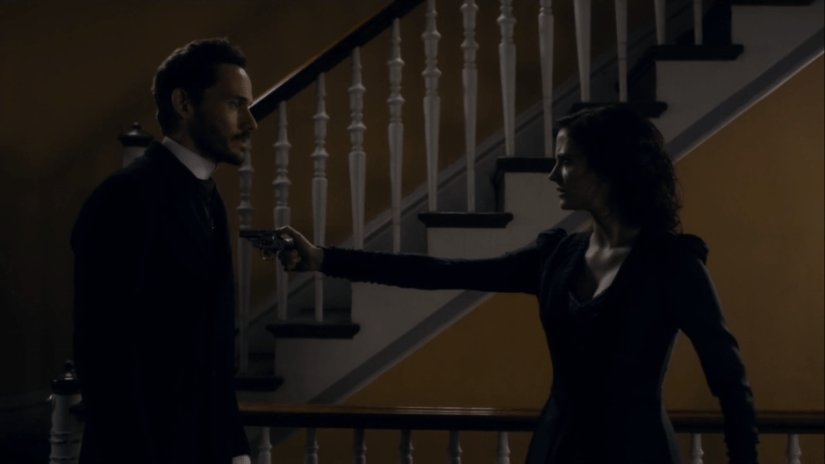

The reason this episode’s exploration of identity was so gripping has much to do with its focus on the season’s central female characters, Vanessa and Lily. Each comes to realise that they were wrong about the central male figure in their life. Vanessa learns the truth about Dracula’s identity, and sets out to kill him. Lily discovers that Dorian Gray will always put himself first (to no one’s surprise). She realises this too late to escape Dorian’s betrayal, and likely too late to escape Victor Frankenstein’s plans to turn her into ’a proper woman’.

The episode plays very effectively with traditional images of deviance and the monstrous feminine; monstrous women and the men who want to define them. As in previous episodes, Lily is Vanessa’s foil. One woman has broken free of the fears and social restrictions that held her back, and must now return to bondage. The other has been trying desperately to be the ideal woman, and to follow the role society laid out for her, only to break down and give in to the darkness. Neither course is depicted as a wholly positive one.

In the first storyline, Dorian realises that he is no longer centre stage in Lily’s life. Worse, his home has been taken over by a revolution. For Dorian, nothing is more tedious, and he expresses his disdain for Lily’s newfound power in the most condescending way possible:

’What I am is bored. I’ve lived through so many revolutions, you see. It’s all so familiar to me. The wild eyes and zealous ardor, the irresponsibility, and the clatter. The noise of it all, Lily. From the tumbrils on the way to the guillotine to the roaring mobs sacking the temples of Byzantium. So much noise in anarchy. And in the end it’s all so disappointing.’

The episode suggests that men like Dorian, with the privilege of watching and waiting as revolutions come and go, are complicit in the failure of social change. His solution to Lily’s revolution, after all, is to turn her over to Frankenstein. Monstrous women are dangerous, and must be tamed. ‘We’re going to make you into a proper woman’, Frankenstein tells Lily ghoulishly. She will be empty of pain and anger, and instead full of poise and serenity. Here the horror (with a touch of science fiction) is on full blast. The message is somewhat heavy-handed, but powerful nonetheless.

Vanessa, likewise, feels like she is on the brink of both revolution and revelation this week. She visits with Miss Hartdegen who, as hoped, is the agent that allows Vanessa to discover Dracula’s identity. Hartdegen knows the real story of Dracula, which is that there is no real story. ‘All the legends about Dracula are by small-minded peasants and poets and theologians trying to make sense of something utterly inexplicable to them’, she tells Vanessa. They can’t be trusted. The only thing she can be sure about is that Dracula ‘dwells in the house of the night creatures’. This is a cryptic clue to Miss Hartdegen, but Vanessa knows immediately that Dracula and Dr Sweet are one and the same.

The encounter between Dracula and Vanessa in the taxidermy museum mirrors the relationship between Ethan and Hecate in many ways. Vanessa and Ethan struggled to stay in the light, on the side of good, while Dracula and Hecate tempt them with darkness, calling them to become their ‘true selves’. Stop being ‘what you thought you ought to be. What your church and your family and your doctors said you must be’, Dracula tells Vanessa. ‘There’s one monster who loves you for who you really are. And here he stands’.

The fact that the genders are reversed in this instance makes the episode’s twist – that Dracula doesn’t want Vanessa to serve him, he wants to serve her, the ‘mother of darkness’ – infinitely more interesting.

In her book The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (1993), Barbara Creed describes the way that women have historically been ‘constructed as “biological freaks” whose bodies represent a fearful and threatening form of sexuality’ (p. 6). Creed also distinguishes between the monstrous feminine and the female monster, arguing that femininity has its own, distinct brand of horror. From a feminist and psychoanalytic perspective, she describes seven guises of the monstrous feminine: archaic mother, monstrous womb, vampire, witch, possessed body, monstrous mother and castrator. Lily has been nearly all of these things at one point or another, and so has Vanessa. And now, we discover a potential reason for Vanessa’s surfeit of feminine symbolism – she is not simply a monster, she is the mother of all monsters.

This emphases on the monstrous feminine has tweaked my perception of the episode’s male monsters as well, and essentially of the entire season. The season was originally set up as a conflict between men, between vampires and werewolves, but given this week’s twist anything could happen. In the end, ‘Ebb Tide’ was chock full of twists and revelations, but it feels more like a setup for things to come than a standalone episode.

I’m excited to see where they ultimately lead us in next week’s grand, two-part season finale.

Notes

- ‘So it’s a love story, is it?’ ‘You know it is.’ Penny Dreadful for plays on the cinematic trend of romanticising Count Dracula, albeit in an unexpected way.

- Creed also argues that man fears woman as castrator, rather than as castrated, as psychoanalytic theory often suggests. Again, this understanding of the monstrous feminine applies metaphorically to Vanessa (who can apparently bring even Dracula to his knees), and more literally to Lily (who tells her army of prostitutes bring her the severed hands of ‘bad men’).

- There’s a lot one could say about this episode’s images of passive, prone women, and its deployment of the male gaze (see Laura Mulvey).

- It seems from the Apache prophecy like it will boil down to vampire versus werewolf after all—Ethan versus Dracula. At least it seems like Vanessa may be in charge of deciding who wins. Honestly, I would be most happy to see her reject both suitors.

- ‘We will not always be hungry.’ The opening scene—where Lily visits the grave of Brona’s daughter, Sarah Croft—was pretty great, despite my frustration that the show is assigning Lily yet another stereotypical role.

- John Clare’s side story was, again, seemingly unlinked to the rest of the plot. I can’t escape the feeling that something terrible is going to happen to his family (again) before the season is through.